Seeing Pong for the first time, a young Kahlief Adams thought Oh, my God! These two lines and this one dot moving across the screen…this is the best thing on the planet! “And now, we’re building full worlds.”

He’s wanted to make games for as long as he can remember.

“I’m lucky enough to have found a hobby that I’ve made into a career, a space, and a platform to talk about a thing that I love, a people and culture that I love, about how those things are connected.”

A senior community manager for a video game studio in Bellevue, just east of Seattle, he’s also worked in development and the diversity and inclusion sectors of the business. Over 13 years in the industry, Adams, 44, has seen positive change.

“We have more Black or brown protagonists on the front of a box. When I was growing up, that was never the case.”

But cosmetic, customer-facing improvements like these have only delayed the vitally important internal work. Adams said, after all this time, Black representation is still inadequate and year after year colleagues at the table still don’t look like him.

Compared to its technological advances, culturally, the industry has moved at a sloth’s pace. To reflect its workforce and consumer base, Big Gaming has far to go along the racial spectrum.

Props, Punts, and Accolades

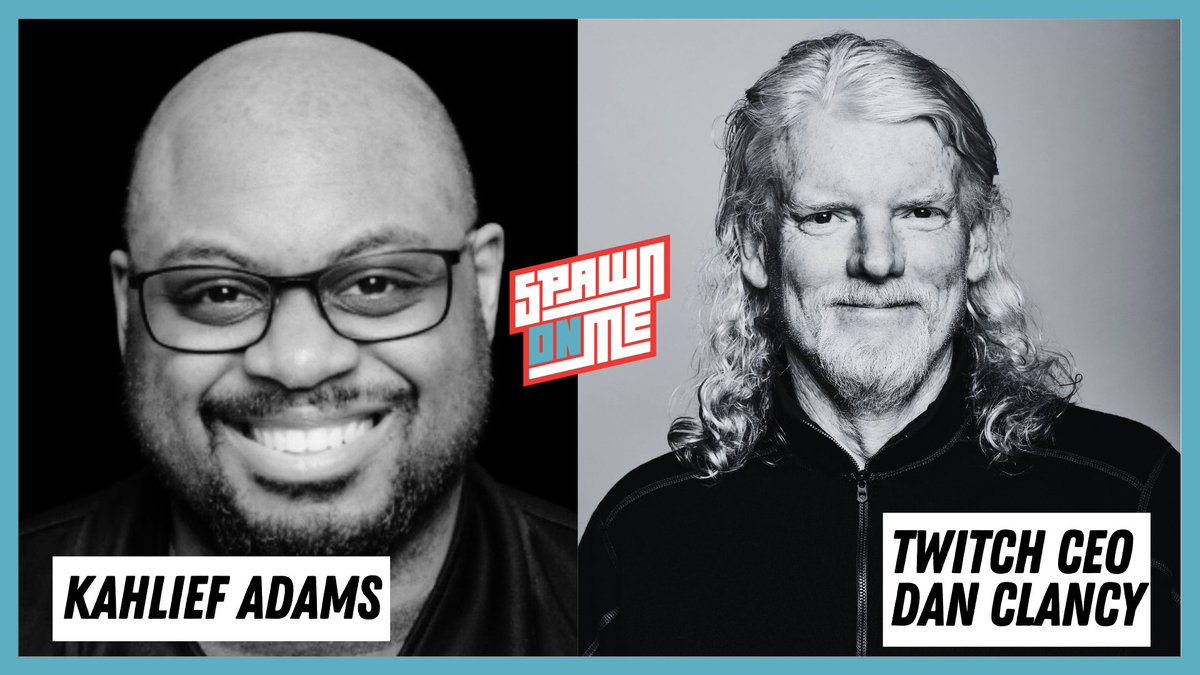

Spawn on Me, Adams’ podcast with co-host Riana Manuel-Peña, was born to accelerate that progress. “Black and brown folks move things forward,” he said, “And we’re the most innovative people on the planet.”

For ten years running, the show has woven together elements of Black and brown culture with everything gaming. Guests appearance include Evan Narcisse, formerly a writer for Kotaku, now Marvel; Erin Ashley Simon, part owner of the esports org XSET; Parris Lilly, co-host at Gamertag Radio, which has featured podcasts hosted by underrepresented people for almost 20 years; and recently, Dan Clancy, CEO of Twitch.

Spawn On Me airs Wednesdays on all the usual platforms. The Spawnies annual award show, an appreciation for contributions from Black and brown industry pros, happens each January.

We Outchea

For a significant segment of the consumer base, the gaming experience is balanced on the accurate and comprehensive presentation of Black people in games.

The industry has shown its dedication to telling interesting stories but, cultural portrayal is about much more than pictures on a box.

“Black folks know white culture because we live in it all the time” at work and at play, said Adams, who lives in Portland, Oregon.

White people in America, on the other hand, generally perceive Black humanity and culture through stereotypes portrayed in media, and through fears of retribution in light of American history.

The richness and relevance of Black culture and its global histories simply cannot be accessed or understood from these positions, so, ultimately, because of the scarcity of Black makers in the space, the heart, mind, and soul of blackness are often not reflected in games that make it to market, Adams said.

There’s no shortage of fantastic and familiar characters with new stories to tell. “We’re playing in fantasy worlds. If [we] want to make Superman Black, [we] can. He’s an alien!” Players adore the Black and Latino Captain Americas, and, importantly, those larger-than-life characters are now in the canon, said Adams.

But the white racial aesthetic has remained an industry standard. It’s the baseline, he observed, even in fantasy worlds shaped in the minds of Japanese designers. The forthcoming Final Fantasy 16, produced by Japanese studio Square Enix, is set in what he called “that European-styled space.”

In notions about what whiteness brings to a space, and otherwise, what detracts, Adams said the stranglehold of white supremacy is revealed.

We Know the Problems. We Know the Solutions.

“How do we make people give a shit?” he asked, and reasonably concluded, “If they care about human beings, they care about Black people.” When that calculus gets difficult, and “they don’t want to deal with feelings,” Adams said, “they’ll have to deal with facts.”

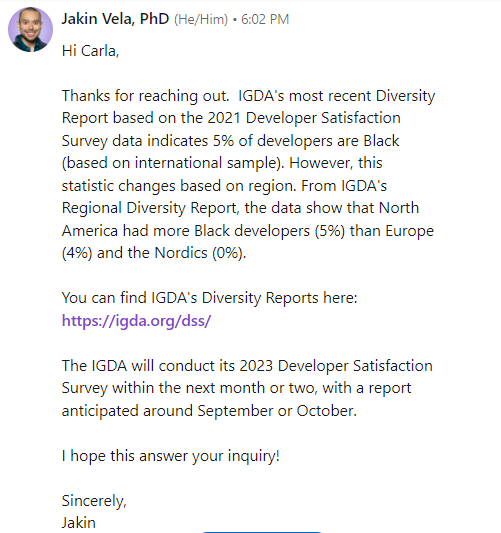

Black people make up 5% of developers in the North American gaming industry. “Paltry numbers,” Adams remarked, confirmed by Jakin Vela, executive director of the International Game Developers Association.

Naturally, such meager representation raises assumptions and forms conclusions among industry professionals and job seekers, as well as the cross section of players, about belonging, worthiness, investment, and support.

Adams admits he’s never liked the ‘business case for diversity.’ It’s a concept packed with commodification, but if it will produce better representation in the industry, if it means “we get to see [characters] who look like us, being heroic,” he said he’ll take it.

Agency + Investment = Authenticity

Among producers of fantasy games, look and feel are, perhaps, most important. Gaming companies want talented people to create gaming environments on par with what we see in film, Adams said, to facilitate a sense of escape through gameplay. In his assessment, this is absolutely achievable, but only by elevating culture from lowest to highest priority, industry-wide.

First, cultural competency. As a standard, portrayals of Black and brown game characters should be written, voiced, and vet by Black and brown creatives, Adams said.

Taking for example Forspoken’s young Black woman character “Frey Holland” from New York City, he noted several issues: beyond her physical appearance, “There was nothing grounding her blackness in that space.” The character was voiced by a British woman. Black, yes, but no — “It just didn’t land.”

Born and raised in the Bronx, Adams’ back-of-hand knowledge of the city meant another mismatch. “The New York layers of the game also failed in regional authenticity.” All of this negatively impacted Adams’ ability to resonate with the protagonist.

When it comes to authentic language, speech, dialect, inflection, and accent, Adams said success depends on proper alignment between voice casting and directing. In the absence of in-house authenticators (read Black employees), he strongly suggests hiring a consultant, and timing matters here. When Square Enix brought Black Girl Gamers in on Forspoken, the project was already in late-stage production.

Second, marketing dollars. Industry CMOs are encouraged to understand and appreciate the massive power honed by the community of Black gamers.

“Black folks [comprise] a huge part of the spending block…in the video game space,” still, he said, with the exception of Black History Month, “this multibillion-dollar industry doesn’t market to the Black gaming community, even when prominent game characters are Black.”

Third, agency. The gaming industry should cultivate environments where Black creatives are earnestly recruited and, once hired, invited and empowered to bring criticisms and make adjustments that hold sway, without threats to career opportunities and mobility.

The superior gaming experience will result when the right people are doing the work. They carry cultural know-how and lived experience, and are fluent in the nuance of unspoken things.

“Like a video game version of the head nod,” Adams imagines, conveying, ‘I see you, too.’